Public Transportation Post-Peak: Shared Public Health Risks, Shared Responsibility

June 9, 2020

THE COMMONWEALTH COMMUTES

Written by Caitlin Allen-Connelly, Project Director1

FACTORS INFLUENCING DEMAND FOR PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION POST-PEAK

After two months of lockdown, the Commonwealth is preparing to reopen under Governor Baker’s four-phased reopening plan. The plan, presented on May 18, 2020, calls for a very gradual return of non-essential workers to the workplace, capping office capacities and encouraging continued teleworking, if applicable. The early phases of this plan prioritize public transit for essential workers, as well as non-essential workers that cannot telecommute—the MBTA is not slated to resume full service until Phase 3. As travel restrictions are lifted and full service resumes, non-essential workers will begin to assess the safety and feasibility of their once rote commutes.

In Greater Boston, public transportation is one of the most important components of a successful reopening of the economy. It is the sole link—the connector—for many residents to their jobs and livelihoods. Pre-COVID-19, more than 500,000 people took 1.18 million trips on an average weekday in Massachusetts, including low-income (28.8% across all modes, 41.5% on buses and trackless trolleys) and minority riders (34.3% across all modes, 48% on buses and trackless trolleys, 41.7% on the silver line).2 3 Total ridership has plummeted by 85% during the pandemic with stay at home orders and service prioritization for essential workers.4 Across the country, and no doubt on the MBTA, the make-up of public transit riders has also shifted, with an increase in women (56%) and a decrease in white transit users (50% reduction). As one result of this shift the current majority of users are Black and/or Latino.5

A recent Transit survey suggests that 9% of transit users have a car, an additional 6% have access to a car, and the remaining 85% of users depend on public transit (with access to cars lowest amongst low-income users). As the economy continues to reopen, therefore, there will inevitably be an uptick in transit demand.6 What exactly ridership will look like post-surge remains an unknown, but it is critical that MBTA put in place measures that ensure the safety of all riders as well as the system’s workforce. The current COVID-19 response measures cater to lower ridership and frontline workers, and more stringent measures will be necessary to gradually accommodate a safe return to the workplace for people who are currently teleworking or using a non-public transit mode to commute.

An initial survey by Suffolk University indicated that only 18% of people would be comfortable riding public transportation as they return to the workplace.7 However, recent polling results from MassINC show that many previous public transit users in the Commonwealth will not return to their normal commuter modes, i.e. the commuter rail (-28%), subway (-29%), and bus (-30%), at least in the short term, when they go back to their workplaces.8 There are many factors that will influence post-peak public transit use. The MassINC poll suggests that a person’s ability to telework is a primary factor (41% polled would prefer to work from home), followed by mitigation of public health risks on the transit system, including in stations, on platforms, and in vehicles.9

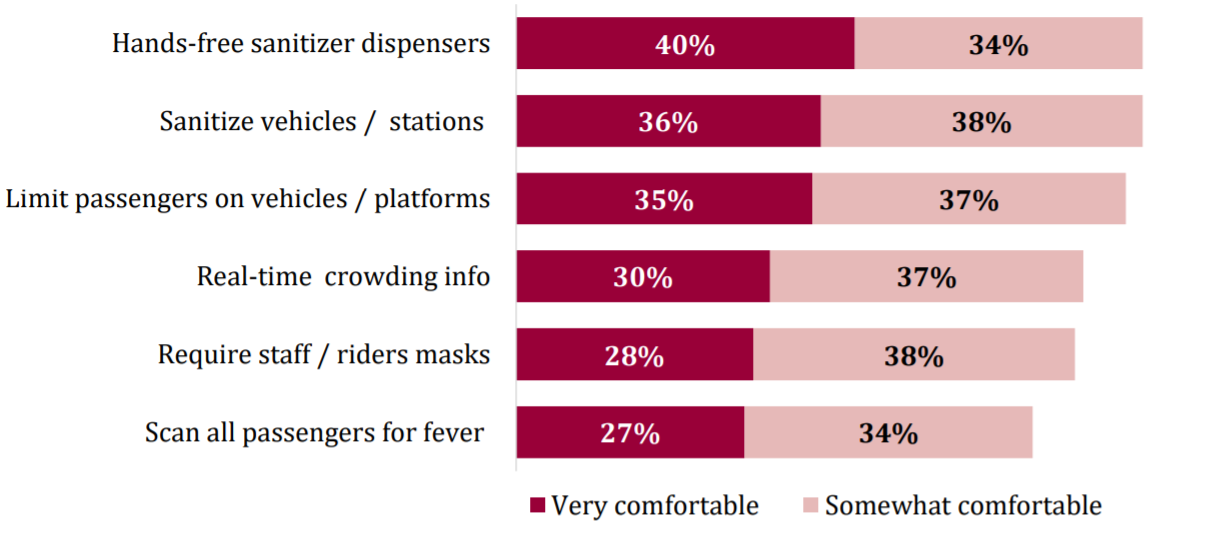

FIGURE 1: WHAT RIDERS WANT FROM THE MBTA BEFORE GETTING BACK ON PUBLIC TRANSIT

Source: The MassINC Polling Group – Taking precautions would make residents more comfortable on transit - % who say they would feel comfortable riding transit if specific precautions were taken

While a good portion of the workforce in Massachusetts may not return to the workplace in Phase I or II of the Commonwealth’s reopening, it is critical, and never too early, to start providing riders with the facts on (1) public health risks associated with public transit, and (2) actions taken by transit agencies to reduce these risks. This piece focuses on the public health risks associated with public transportation and the shared responsibility between transit agencies and riders to minimize them. It also seeks to underscore the need to ensure safe public transportation for all riders.

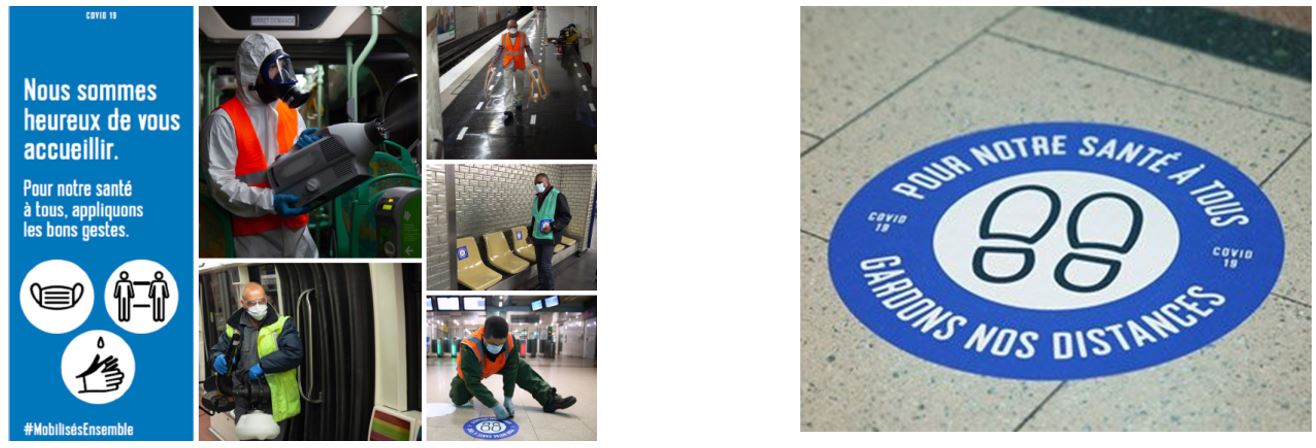

Across the globe, public transit systems are instituting public outreach and education campaigns as a call for collective action to create the safest commuting environment possible. Public transit riders in the Commonwealth would benefit from a similar information and outreach campaign (multilingual and multimedia), as well as targeted health and safety guidelines for riders throughout the four reopening phases, to support a joint approach between transit agencies and riders to commuting post-COVID-19 peak.

Note: In Paris, “Pour Notre Santé a Tous” or “For All of Our Health” frames the return to public transit system as a shared responsibility.

Note: In Paris, “Pour Notre Santé a Tous” or “For All of Our Health” frames the return to public transit system as a shared responsibility.

THE FACTS ON PUBLIC HEALTH RISKS & PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION

Before getting back on public transit, commuters should have the facts about the health risks they may face when riding. The basic assumption has been that there is a correlation between public transit use and spread of infectious diseases, but research on this topic is limited. This analysis builds off available scientific literature on the transmission of influenza-like viruses on public transit and recent articles and papers on the correlation between SARS-CoV-2 and public transportation.

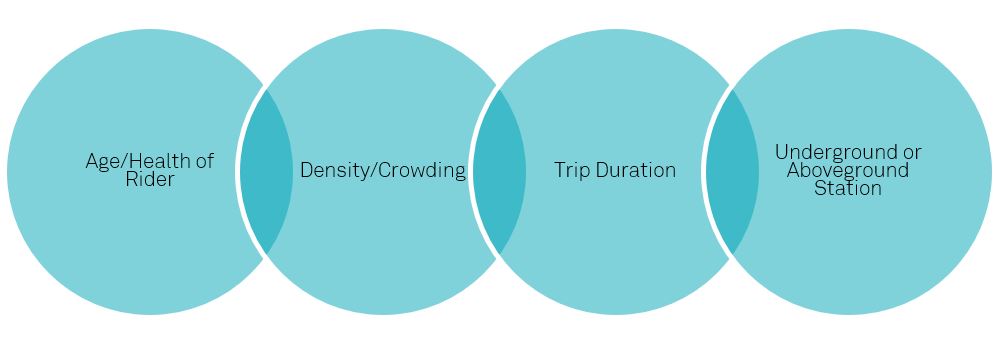

Scientific research shows that closed, poorly ventilated, and crowded environments can act as hotspots for spreading disease; therefore, riding on public transit that meets this description comes with potential health risks.10 The main factors thought to influence direct and indirect transmission of the disease on public transit include the health and age of the passenger, the number of passengers on board (density, crowding), the amount of time riders are on the system (trip duration), and the extent of contact with infected surfaces.11 Recent research suggests that the type of station (underground or aboveground) also plays a role, stipulating that riders are more vulnerable to transmission when using underground stations than when their commute relies primarily on aboveground stations (average influenza-like illness (ILI) 7.61 per 100,000 contacts, compared to 10.24 ILI per 100,000 contacts on underground lines).12 13

FIGURE 2: KEY FACTORS INFLUENCING SARS-COV-2 TRANSMISSION RISK ON PUBLIC TRANSIT

A recent example from China involving two buses (one with an asymptomatic passenger and another with no infected passengers) shows the risk of transmission in confined spaces, including mass transit, and the resulting importance of wearing facial coverings, practicing physical distancing, and ensuring proper cleaning, disinfection, and ventilation to prevent the spread of disease. On one of the buses (bus 2, capacity 75, carried 67 passengers), there was an asymptomatic passenger who later tested positive for the coronavirus. The other bus (bus 1, capacity 75, carried 59 passengers) carried no infected passengers. Both buses had air conditioning with indoor recirculation mode on and brought people to the same venue, where they interacted. Twenty-four out of 67 people on bus 2 that carried the asymptomatic passenger got sick. No one who traveled on the other bus got sick.14

WHY PHYSICAL DISTANCING, FACE COVERINGS, AND PERSONAL HYGIENE ARE

|

|

| TRANSMISSION METHOD | DISTANCE CARRIED (DROPLETS) |

| Breathing or talking | Up to 1 meter (~3 feet) |

| Coughing | Up to 2 meters (~6.5 feet) |

| Sneezing | Up to 6 meters (~19.6 feet) |

Source: Adapted from Goscé and Johansson Environmental Health (2018) 17:84 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0427-5

According to the CDC, transmission of the coronavirus occurs much more commonly through respiratory droplets than through objects and surfaces, but it is unknown how long the air inside a space occupied by someone with confirmed COVID-19 remains potentially infectious. Additionally, current evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may remain viable for hours to days on surfaces made from a variety of materials. As a result, public transit riders are susceptible to both direct and indirect transmission while they are commuting. 16 17 18

- DIRECT TRANSMISSION occurs through inhalation of large respiratory droplets through the mouth or nose. When a rider breaths or talks, large droplets can be carried up to 1 meter (~3 feet), and when a commuter coughs they can be carried up to 2 meters (~6.5 feet), and when someone sneezes up to 6 meters (~19.6 feet), potentially exposing another rider to the virus.19 Under controlled experiments, the environmental stability of SARS-CoV-2, is up to three hours in the air post-aerosolization, which means that it does not dissipate immediately and can continue to be inhaled after a person breathes, sneezes, coughs, etc. 20 21

- INDIRECT TRANSMISSION happens through contaminated fomites, i.e. common touch surfaces. Tests under laboratory conditions suggest that the virus may survive for four hours on copper; up to 24 hours on cardboard; and up to two to three days on plastic and stainless steel. These times may be lower in open environments. 22 23

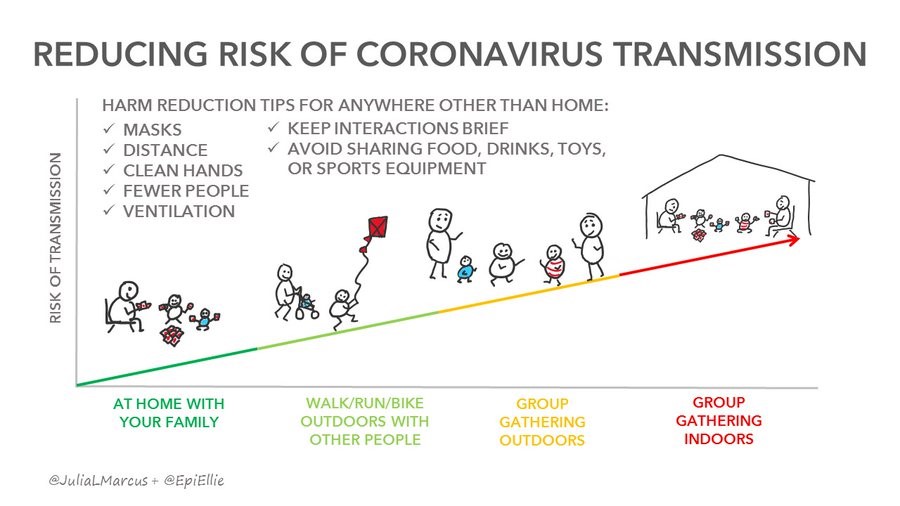

Source: Julia L. Marcus, PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor in the Department of Population Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, and Adjunct Faculty at The Fenway Institute, Professor Ellie Murray, Boston University School of Public Health (https://twitter.com/JuliaLMarcus/status/1262448399888142337?s=20) / https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2020/5/22/21265180/cdc-coronavirus-surfaces-social-distancing-guidelines-covid-19-risks

TABLE 1: QUALITATIVE RISK ASSESSMENT FOR TRANSPORTATION SETTINGS

CATEGORY |

CONTACT INTENSITY |

NUMBER OF CONTACTS |

MODIFICATION POTENTIAL |

| Buses | High | High | Medium |

| Metros/Rail | High | High | Medium |

| Rideshare/Taxis | High | Low | Low |

Note: While public transportation does rank high for contact intensity and number of contacts, agencies do have a fair potential to mitigate these risks by putting in place physical distancing protocols, engineering responses, and PPE protocols

A SAFE COMMUTE DEPENDS ON ALL OF US

Because there are risks to transit riders and operators, public transit agencies have a responsibility to take adequate steps to ensure public health on the system, including robust cleaning and disinfecting protocols; face coverings for workers and riders; creating and ensuring adequate physical distancing in stations and on vehicles; and improving ventilation.24 However, this responsibility is a shared responsibility with the riders it serves. Transit agency measures alone will not ensure a safe commute.

Commuting in the post COVID-19 world comes with a new set of rules and a call for collective action to jointly create conditions that prevent the spread of the disease on public transit. This means moving from an “I Commute” attitude, to a “We Commute” mentality. More than ever, public transit riders are an integral part of the solution to ensuring a safe commuting environment.

There are proven ways for public transit users to protect themselves and their fellow commuters, which dovetail with the main approaches that transit systems will likely adopt, specifically on 1) cleaning and disinfecting, 2) face coverings, and 3) physical distancing, as well as some other hygiene tips that further empower riders to safeguard the shared commute.

BEST PRACTICES FOR A SAFER, SHARED COMMUTE

- STAY HOME WHEN SICK: One of the most important measures riders can take is to stay home and not use public transit if they are sick. The coronavirus is highly contagious and easily spread in a confined, indoor environment.

- PRACTICE HAND HYGIENE: Hand hygiene protocol is also an important tool for riders when they get back on public transit. It is a first line of defense. Carry hand sanitizer with you at all times (>60% alcohol, with 60%-70% ideal) and use it before and after your commute. When applying, cover all surfaces of your hands and rub them together until they feel dry (avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands), and wash your hands for at least 20 seconds as soon as possible after being on public transit, or after blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing. 25

- PRACTICE RESPIRATORY HYGIENE: Cover your mouth with the crook of your elbow or use a napkin or tissue if you have to cough or sneeze to avoid spreading droplets that could escape from a facial covering, but make sure to discard the tissue in an enclosed trash bin afterward.26

- WEAR A FACE COVERING: Face coverings are a fundamental tool to collectively preventing the spread of disease. They ensure that your fellow commuter is protected—in the event that you are infected with the virus. Research suggests that widespread use of face coverings (80% of the population or more) plays a crucial part in helping and possibly stopping the spread of disease.27 Governor Baker’s, COVID-19 Order No. 19, requires any person over age two wear masks or cloth coverings at all times when using any means of mass transit 28 See the recently issued World Health Organization guidance and practical considerations for non-medical mask production and management.29

- PRACTICE PHYSICAL DISTANCING: COVID-19 spreads mainly among people who are in close contact (within about 6 feet) for a prolonged period (direct transmission). It may also be possible for you to get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching your own mouth, nose, or eyes (indirect transmission). Physical distancing helps limit opportunities to come in contact with contaminated surfaces and infected people outside the home.30 The CDC provides guidelines on physical distancing on mass transit; however, commuters will need to create the proper physical distancing space, especially if there are inadequate signage and markers.31

- LIMIT SURFACE CONTACT: COVID-19 is spread indirectly through contamination of surfaces. For public transit this means limiting and eliminating contact with turnstiles, poles, and seats and avoiding touching your nose, eyes, and mouth if you come in contact with surfaces.32

- REFRAIN FROM EATING OR DRINKING: To avoid direct transmission, avoid eating or drinking in stations and on transit vehicles and ensure you are properly wearing a face covering and do not touch your face throughout your commute.33

- AVOID TOUCHING YOUR PHONE: Experts advise against using personal mobile devices while riding public transit. This is because mobile devices are exposed to potential contaminated droplets and if your hands become contaminated, your phone can become a fomite, i.e. common touch surface.34

PLEASE STAY HOME AND OFF THE T IF YOU’RE SICK: HERE’S WHY

If you are SYMPTOMATIC OR HAVE TESTED POSITIVE FOR COVID-19, coughing and/or sneezing, you are putting fellow riders at risk. Why? The droplets in a single cough or sneeze may contain as many as 200,000,000 (two hundred million) virus particles, and if you cough or sneeze, those 200,000,000 viral particles go everywhere. Even if you are not face-to-face with another commuter, your infected droplets can hang in the air for a few minutes and fill a modest sized room (or bus, commuter rail coach, trolley car), which puts other commuters at risk just by breathing.35 If you are PRE-OR ASYMPTOMATIC, you are also putting fellow riders at risk for similar reasons but also because the virus can replicate in eyes and nasal passages via hands, i.e. eye/nose-hand-common touch surface-hand-face.

A NEW, SHARED ERA FOR COMMUTING IN THE COMMONWEALTH

As of publication, Governor Baker and the MBTA have released only high-level guidance on what will be expected of riders over the four phases of the reopening. The guidance issued to date does asks riders, employers, and the MBTA to work together to ensure the safest possible public transit conditions.

- FOR RIDERS: The guidance requires riders to wear face coverings when using public transit, urges riders to maintain physical distance, and urges riders to refrain from using transit if sick.

- FOR EMPLOYERS: The guidance encourages employers to implement staggered hours for employees who must return to the workplace and to continue teleworking policies that will reduce demand and prioritize public transportation for essential workers, especially during rush hours.

- FOR THE MBTA: The guidance calls on the agency to continue to take protective and preventative measures such as frequently disinfecting and cleaning vehicles and stations and providing protective supplies to workers.36

Yes, the return of more non-essential workers public transit and the workplace comes with a shared responsibility by the employers, riders, and the MBTA. Yes, there is a strong public health case to support this approach. However, riders can only do their part if they have clear information on what safety measures the T is putting in place, know the public health risks, and have the knowledge and tools to be part of the shared solution.

Compared to peer agencies in Europe, Asia, and right here in the United States, the guidance issued to date in the reopening plan does not go far enough to provide a safe public transit environment or to educate the rider on what they can do to ensure safe passage for all. As the Commonwealth’s public transit operator, the MBTA must lead the way. The agency should release a comprehensive plan to lay a strong foundation that builds rider confidence and brings commuters back to public transportation that covers all different mitigation strategies for limiting the spread on public transportation.37

To support the implementation of the reopening plan, A Better City recommends that the MBTA's Ride Safer campaign be extensive, far-reaching, and multilingual/multimedia to (1) provide all riders with the information they need to feel and be safe on public transit, and (2) support and coordinate distribution of face coverings and hand hygiene (in stations, on vehicles, on streets) along their commute. These measures will help ensure the MBTA’s current ridership—predominately “essential workers” many of whom are women and people of color,38 —is as prepared and protected as its future ridership. All public transit riders regardless of employment sector status are an equal part of the solution: they are all “commuter heroes” and they all deserve access to the necessary information and protective equipment to continue to use or get back on public transit safely. Together, the MBTA and its riders can pave the way for a social compact to support a strong, resilient, and just public transit system, today, and safeguard this important public good for generations to come.

SOURCES

- Research is limited in the area of public health risks and public transportation, in particular with respect to transmission of viral diseases like SARS-CoV2; however, this piece is informed by the most current published research and guidelines, including Dr. Erin Bromage, Associate Professor of Biology, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, as well as personal communication with Dr. Elizabeth Scott, Associate Dean and Professor, College of Natural, Behavioral, and Health Sciences, Simmons University.

- https://mbtabackontrack.com/performance#/home

- 2015-2017 MBTA Systemwide Passenger Survey

- https://www.wbur.org/bostonomix/2020/05/11/mbta-reopening-service-plan

- https://medium.com/transit-app/whos-left-riding-public-transit-hint-it-s-not-white-people-d43695b3974a

- Ibid.

- https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/05/05/metro/feeling-economic-pinch-massachusetts-residents-remain-resolute-battling-coronavirus-new-poll-finds/

- https://www.massincpolling.com/the-topline/2020/5/27/residents-predict-fewer-trips-in-the-future-plan-to-use-solo-modes-more-as-coronavirus-upends-transportation-patterns-across-massachusetts

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59a6d1d0e9bfdf582649f71a/t/5ece82a5b95b250db4389310/1590592165921/Slides+2020+05+Barr+Transportation.pdf

- Goscé and Johansson Environmental Health (2018) 17:84 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0427-5

- https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/3/13/21177324/public-transit-pandemic-coronavirus

- Goscé and Johansson Environmental Health (2018) 17:84 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0427-5

- Note: The study looks at the infection processes on the very first moments of contagion, limiting the study to 15 minute segment intervals, know that mixing patterns that arise once outside the underground network (households, offices, etc.) will lead to new infections that can blur the public transportation role when looking at the bigger picture. Contact is defined as two individuals in contact if the local density around them is high enough that they enter in the respective infective regions that surround them.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340418430_Airborne_transmission_of_COVID-19_epidemiologic_evidence_from_two_outbreak_investigations

- Ibid.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cleaning-disinfection.html

- https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/coronavirus-airborne-here-s-what-we-know-n1216726

- Goscé and Johansson Environmental Health (2018) 17:84 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0427-5

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- https://www.erinbromage.com/post/the-risks-know-them-avoid-them

- https://www.abettercity.org/assets/images/Going%20the%20Distance%20Report%202020%20FINAL.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faqs/respiratory-hygiene.html

- Note: A recent study suggests that most of the population (80%) needs to wear a mask to bring about the most rapid end to COVID-19 in the UK (Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.13553.pdf)

- https://www.mass.gov/doc/may-1-2020-masks-and-face-coverings/download

- https://nam10.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.who.int%2Fdocs%2Fdefault-source%2Fcoronaviruse%2Ftemp%2Fwho-2019-ncov-ipc-masks-2020-4-eng.pdf%3Fsfvrsn%3D20ec1cbf_2%26download%3Dtrue&data=02%7C01%7Ccallen-connelly%40abettercity.org%7Cf66cff520d934304007a08d80a18ae79%7Cdcca40908abf49669bd98fc41101bf19%7C0%7C0%7C637270448427045084&sdata=xBvTqZBpf6E%2BicZ7TwwgbXHWuEdzQXFMzXBQSzSp7BM%3D&reserved=0

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/pdf/MassTransit-DecisionTree.pdf

- https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-avoid-getting-sick-traveling-trains-subways-coronavirus-2020-3#limit-contact-with-train-and-bus-poles-6

- https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-avoid-getting-sick-traveling-trains-subways-coronavirus-2020-3

- Personal communication, Dr. Elizabeth Scott, 5/20/2020

- Adapted from https://www.erinbromage.com/post/the-risks-know-them-avoid-them

- https://www.mass.gov/doc/reopening-massachusetts-may-18-2020/download

- https://www.abettercity.org/assets/images/Going%20the%20Distance%20Report%202020%20FINAL.pdf

- https://medium.com/transit-app/whos-left-riding-public-transit-hint-it-s-not-white-people-d43695b3974a