Reimagining Our Commuter Rail System with Urban Rail

October 10, 2017

Today, the MBTA’s Commuter Rail system is a regional network that reaches far from downtown Boston. The network consists of 12 main lines and operates according to a spoke-hub distribution paradigm, with the lines running outward from the City of Boston. These lines service the eastern third of the state, and provide important transportation opportunities for half of the communities (175 out of 351) in the Commonwealth.

On September 26, A Better City gathered members and experts to help “Reimagine Our Commuter Rail System.” This included a presentation by Glen Berkowitz, Project Manager at A Better City on the concept of Urban Rail and what it could mean for Metro Boston.

What is Urban Rail?

Urban Rail is the concept of running faster, more frequent train service on the inner core sections on various branches of the commuter rail system. Primarily, the MBTA’s Commuter Rail operates suburban and intercity service at far lower frequencies than its rapid transit lines (which includes the subway and Silver Line bus system). Compared to these rapid transit lines, our commuter rail corridors are relatively underutilized, with stations often spaced far apart.

Exploring the concept of Urban Rail asks us to examine three questions:

- Whether self-propelled, faster passenger cars can substitute for or supplement the traditional heavier, slower, dirtier locomotive approach that the MBTA still exclusively deploys;

- Whether new infill stations can be appropriately sited to serve both existing neighborhoods and new transit-oriented development;

- Whether new, shorter, faster trainsets can be the next most cost-effective way to greatly expand mass transit opportunities within and around the Boston urban area.

I. Can we switch cars?

Going back over 100 years, commuter rail trains in Boston have consisted of a heavy locomotive that pulls a number of passenger coaches. In terms of this 19th century technology, not much has changed other than the locomotives now burn diesel fuel instead of coal. And today the MBTA Commuter Rail system still exclusively uses a locomotive that pulls or pushes passenger rail cars. Contrast that with Commuter Rail systems deployed by peer agencies, such as New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority’s Long Island Railroad, which has long used swift, self-propelled electric commuter train sets on the majority of its vast network.

The alternative to the push-pull model is self-propelled passenger coaches, often referred to as Diesel Multiple Units (DMUs) and, down the road, Electric Multiple Units (EMUs). Think MBTA Green Line vehicles, but with the rail cars designed and constructed to meet commuter railroad standards. These would likely be two coach car sets and are already in use in other areas of North America, including Toronto, Canada (implemented in 2015) and Marin County, California (which commenced operations in August 2017.

II. Can new infill stations be appropriately sited to serve both existing neighborhoods and new transit-oriented development?

More frequent station spacing would help enable a new Urban Rail system overlaid onto parts of our commuter rail system. DMUs and EMUs accelerate and brake faster than locomotive-drawn trains and so stations can be closer together and travel times reduced. In fact, such more frequent stations would not be new to Boston. An Early 1900s map of the Boston & Albany Railroad line (what we today call the MBTA’s Worcester/Framingham Branch) shows four stations within the City of Boston BEFORE downtown (Huntington Ave. and South Station) whereas today there are only two at Yawkey and at Boston Landing, which opened in May 2017 (with thanks to the New Balance company which built and paid for it).

III. What about the costs? Isn't the Commuter Rail the most heavily subsidized mode in the MBTA's portfolio?

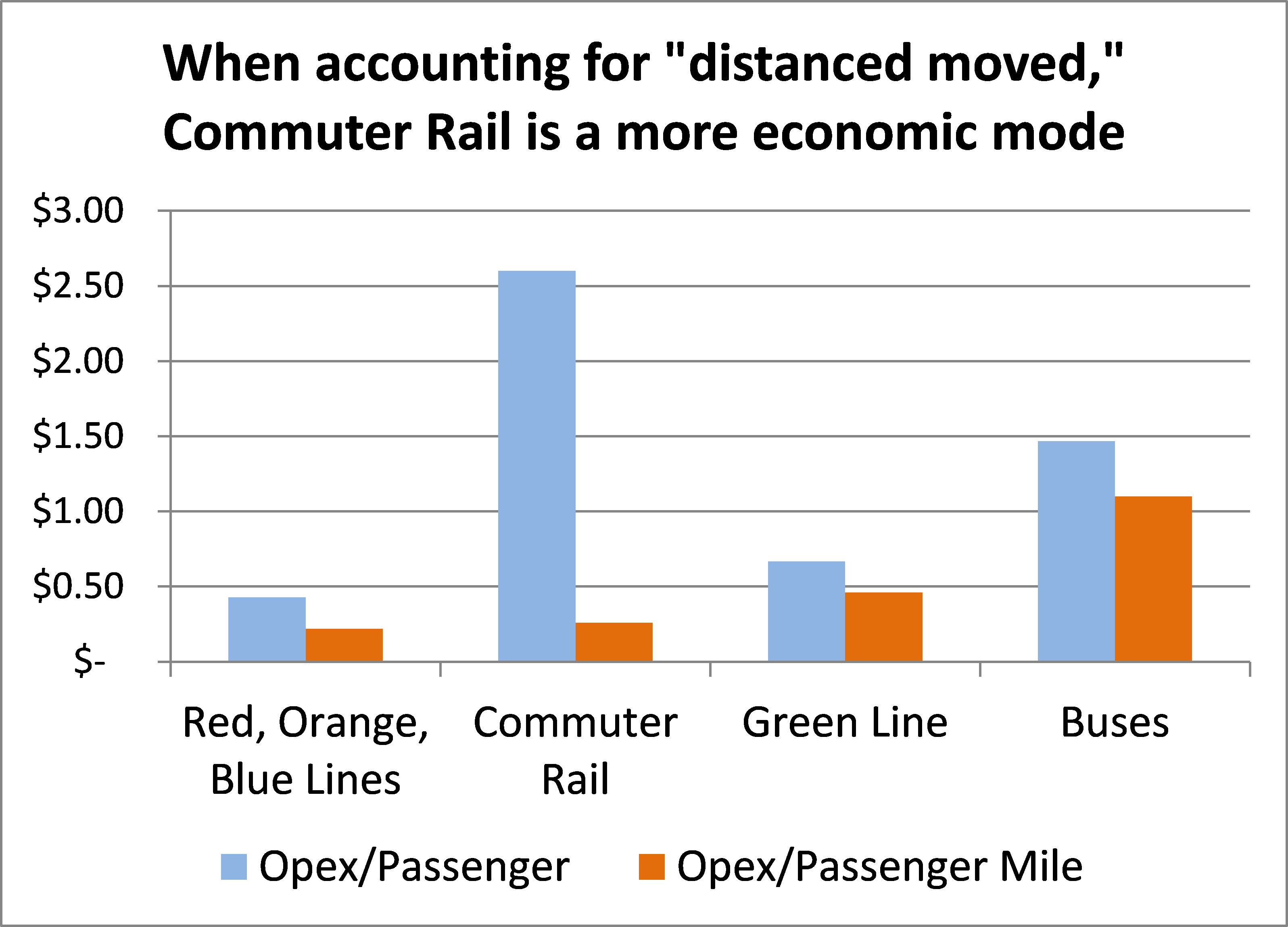

Like many data points and financial metrics, this answer depends on what you’re looking at. When using just the operating expenses as costs, the commuter rail services comprise 26% of the MBTA’s operating subsidies while serving only 10% of its ridership. That doesn’t look too good.

A better suggestion could be to use a metric that accounts for the distance differentials in the ridership, i.e. – how many miles do these subsidies move people? (With thanks to Ari Osevit, a transportation colleague, for his tutelage on these numbers.) When we look at the subsidy per passenger mile, the Commuter Rail doesn’t look as bad. The MBTA’s Heavy Rail (Orange Line and Red Line and Blue Line) service looks the best in terms of operating subsidy per passenger mile but the commuter rail is next best. This should inform our conversation about commuter rail service enhancements.

But is it feasible for Greater Boston?

This wouldn’t be entirely new technology, nor an entirely new way of thinking of the rail system in Boston. In fact, diesel powered self-propelled commuter rail coaches used to be a major part of the commuter rail system. Between 1949 and 1962, a fleet of Rail Diesel Cars (built by the Budd Rail Company of Philadelphia) were used in the Boston area (and many other cities) for short-haul, faster, and frequent commuter service.

A big benefit to the self-propelled coaches is that they were less expensive to operate than the traditional locomotive-drawn train. Urban rail systems today, for the most part, deploy modern versions of similar self-propelled rail coaches that we were using over a half-century ago.

Also, one other note about the frequently-spaced stations in Boston that used to exist on what is today the MBTA’s Worcester/Framingham Branch. Mostly built in the late 1800’s, these stations were often designed by prominent architects, including H.H. Richardson, prior to the age of highways. Most of these historic train stations were demolished in the late 1950s and early ‘60s by the Mass Turnpike Authority to make room for the new six-lane highway in this area. It may be some talk about back to the future, but the maps that we envision for our future Urban Rail would look similar to maps from 100+ years ago….

We also wouldn’t be the first region in recent times to procure such modern self-propelled passenger cars for more frequent service. In 2015, Toronto’s urban rail service opened and in 2017, the Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) system in California began service of seven two-car train sets on their lines. Both Toronto and Marin County procured the trainsets from Sumitomo Corp of America/Nippon Sharyo for ~$7-8 million per two-car set. By contrast, the MBTA pays about $20 million for each new commuter rail train set (consisting of a locomotive and six passenger coaches). Both of these systems mainly run the DMUs in two and three-car sets but they have the capability to be coupled into longer trains as need be.

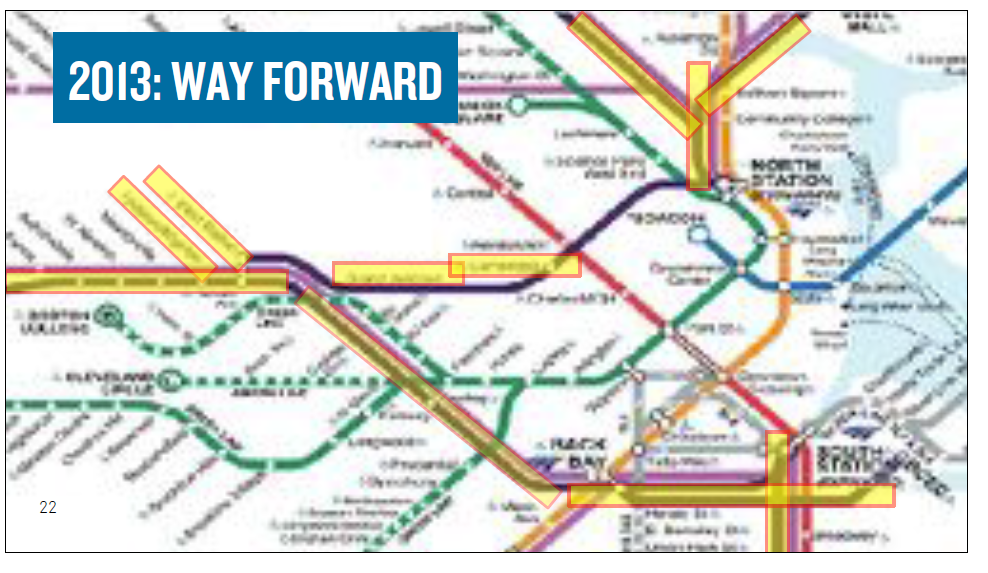

Just a few years ago, we were on our way to making urban rail a reality. As part of their A Way Forward plan in 2013, the MBTA announced that it would create six new urban rail lines known more formally as the Indigo line service. The plan called for creating a second new station on the Worcester/Framingham branch in Boston called West Station near Boston University’s Commonwealth Ave. campus and Harvard University’s 100-acre Beacon Park Yards project. A procurement order was put in place for the requisite DMUs for the first part of the project. However, the Commonwealth canceled this program and procurement in 2015.

What are the next steps if we want to make this a reality?

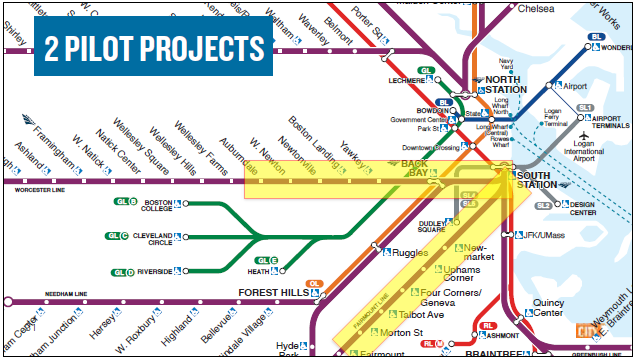

A Better City’s vision is that the MBTA should take steps to move forward with urban rail service as soon as possible. In order to begin, we recommended two pilot projects for new urban rail service to/from Boston’s central business district on this existing infrastructure:

1. Fairmont Line – Points Southwest to Readville

2. Charles River Corridor (Worcester/Framingham Branch) – Points West to Auburndale (Route 128)

If we commit to building the proposed new West Station on the Charles River Corridor - even in temporary condition - as part of the upcoming MassDOT I-90 Allston Interchange reconstruction project, along with using the already in place stations on the Fairmont Line, we could easily implement these pilots and produce better service for the customers as well as valuable insight for MassDOT’s upcoming Commuter Rail Vision Study.

By: Kathryn Carlson, Director of Transportation

kcarlson@abettercity.org