Global Models for Commuter Rail - Recap

November 28, 2018

On November 14th, A Better City welcomed global transit experts to discuss lessons learned in reimagining and rebuilding regional rail systems as part of the Partners in Public Dialogue series at the Old South Meeting House.

Isabel Dedring – Former Deputy Mayor for Transport and Deputy Chair of Transport for London and current Global Transport Leader at A Better City member firm, Arup – and Anna Pace – Former Director of Project, Planning and Development for Toronto’s Metrolinx- joined Bruce Mohl – Editor of Commonwealth Magazine – for a conversation about what Metro Boston can learn from their experiences in transforming regional rail systems in London and Toronto.

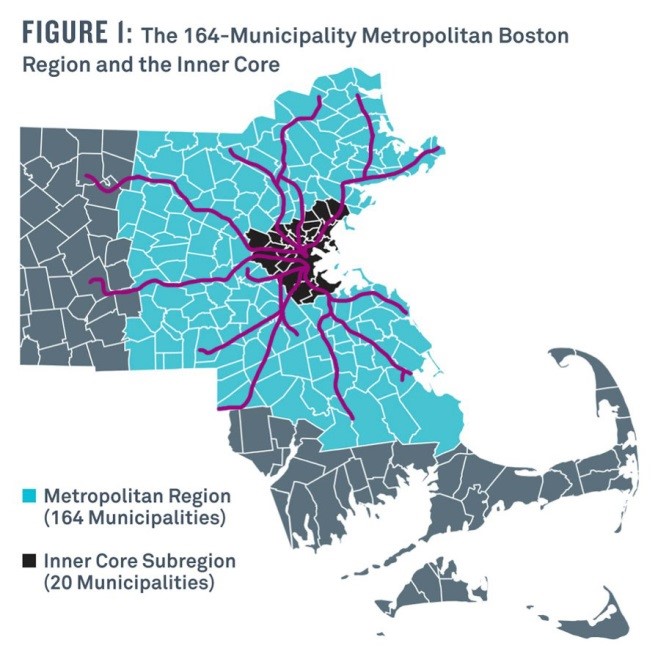

Commuter rail service into and out of downtown Boston serves as a vital element in the region's economic success. As housing prices in the urban core continue to rise and as available land becomes scarcer, workers will look to live further and further from the city, all while continuing to effectively reach jobs in key inner core clusters. Furthermore, improved connectivity throughout the Metro Boston commuter rail region could unlock economic growth potential in Gateway Cities and other regional economic centers. The Massachusetts economy is driven by Metropolitan Boston. The 164-community region claims 69% of the state’s population, 74% of its jobs and generates 84% of its gross domestic product.[1]

Our commuter rail system touches this whole metro area and beyond with 388 route miles over 14 lines that move almost 130,000 people per day, or 10% of the MBTA systems ridership. This infrastructure, these right-of-ways and this reach would be almost impossible to replicate today, not only in direct build cost but also in terms of land acquisition and opportunity costs.

The challenge is to move from a “commuter” system, one built around a 20th-century work structure of a 9-5 suburb-to-city center commute, with limited mid-day and off-peak service to a regional system that provides continuous connection opportunities across the area. Furthermore, we’re running dirty and cumbersome equipment that is out of step with service enhancement goals as well as climate and carbon emission goals.

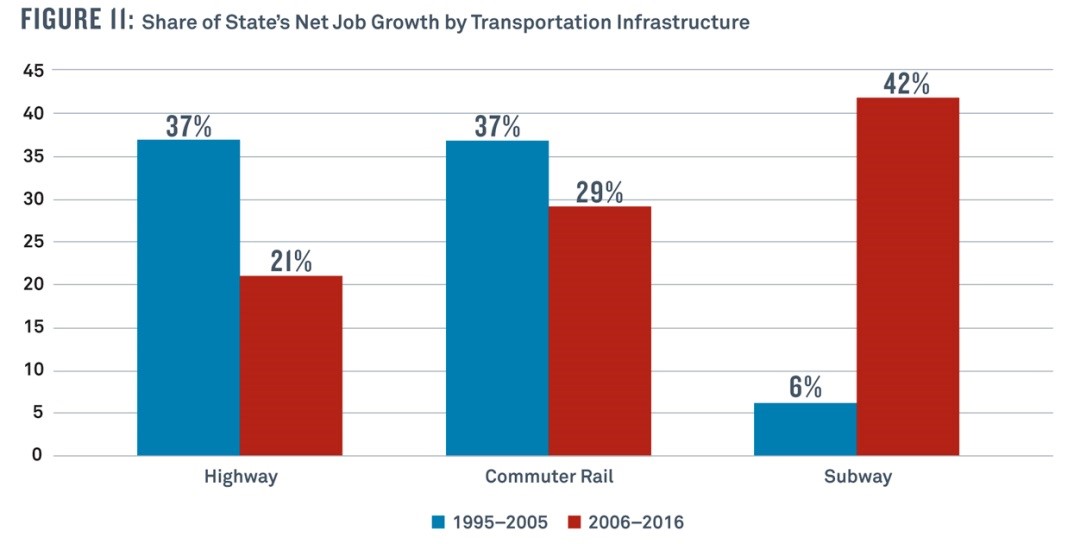

Especially compelling is the shift in economic development and job growth near rapid transit hubs and away from the auto-centric growth of the 20thcentury. Rapid transit enables denser development both at the commercial and residential levels, which leads to agglomeration effects: when the clustering of businesses and the expanded labor pool reduce transaction costs and builds knowledge and human capital nodes with spillover effects.

Anyone who has experienced the clustering in places like Kendall Square, the Seaport or the Longwood Medical Area knows the power of agglomeration and transportation infrastructure. Businesses located in more exurban areas are moving to urban core because the nature of work is changing and they want access to a specialized and dynamic labor market.

While there have been numerous examinations of structural issues around the commuter rail system, MassDOT is currently in the process of completing a long-term visioning effort, the Commuter Rail Vision Study, to be completed by the end of 2019. This conversation with representatives from London and Toronto allowed us to hear about the goals, outcomes, and lessons learned in two peer urban environments to inform our process and guide us to a world-class system.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

Electrification is key: The MBTA’s current commuter rail service is operated by a fleet of diesel locomotives. Not only are these dirty and undermine our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they are cumbersome and do not allow for improved frequency of service. Electric Multiple Units (EMUs) accelerate and brake faster than locomotive-drawn trains and so stations can be closer together and travel times reduced.

Frequency improves ridership. Both London’s Overground rail system and Toronto’s Go Toronto system are providing two-directional full day service with 8-minute headways in London and 15-minute headways in Toronto (compare that to Boston’s 20-minute peak/60 minute off-peak headways.) This level of frequency and service allows people to ride the system on a “turn up and go” basis similar to rapid transit and not based on whether or not a particular schedule works for them. Toronto, for example, while still in the midst of completing the full project overhaul has increased service 2x during peak and 4x during off-peak. And London saw a 5x ridership increase on the fully expanded system with a doubling of ridership on a like-for-like basis. These types of ridership improvements can help address fare equity issues as well.

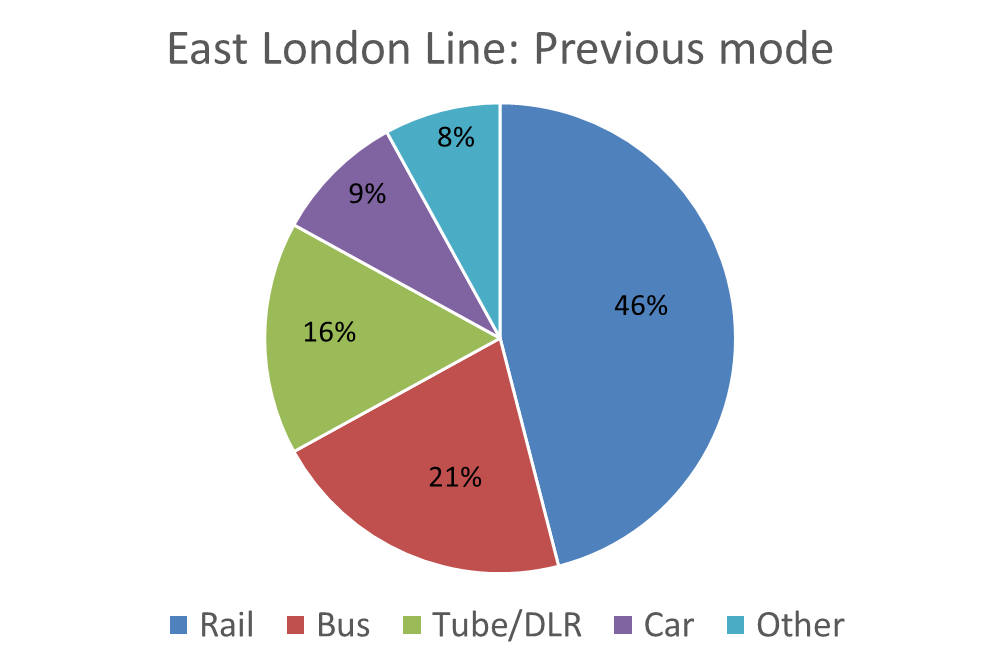

Furthermore, London has seen a 9% mode shift away from private automobile to the rail system, a large move when you consider that 85% of London’s morning commute is already on their regional rail and rapid transit systems.

Hybrid operating models have been successful. While London’s Overground system is operated and maintained via private contractors, Transport for London retains control of strategic planning, project management, marketing and communications, customer service, train service oversight and revenue risk. Isabel Dedring made the point of noting that shorter contract periods (7 years with 2-year extension potential) and an interventionist approach from the public agency have yielded a successful public/private model.

Investment approaches can vary. London completed their 2.5 billion pound overhaul of the 75-mile Overground system in increments over 10 years. This allowed them to show success and demand on one line such that it induced demand for the improvements on other parts of the system and created positive momentum.

Toronto, on the other hand, has approached their overhaul as one large $16 billion over 10 years project branded “Big Move,” which will provide the transformation of GO Transit from a peak only commuter system to a faster, frequent all-day two-way system Regional Express Rail to connect communities. As Anna recounted, the head of Metrolinx determined that “if we’re going to be building a whole new system on top of our current infrastructure, let’s do it right.”

Bold vision for a major overhaul or incremental updates that improve public support has allowed both London and Toronto to reach the ultimate goal, a cleaner, faster more connected system that provides “undeniable benefits in terms of local economies, equity, and property value.”

Thank you to all who joined us for this event and please reach out for further information.

[1] A Better City. “The Transportation Dividend.” 2018.

Review the event slides here.